I recently watched two sustainability documentaries – Cowspiracy, about the devastating environmental impacts of the agricultural industry and our meat-and-dairy intensive diets, and Before the Flood, Leonard Di Caprio’s impassioned plea for us to realise the seriousness of climate change and take urgent action.

Both films got me thinking about why we as human beings are so bad at acting on sustainability, when failure to do so threatens our own wellbeing, not to mention the lives of billions of other people and species. We truly are living in ‘The Age of Stupid’ (as another sustainability documentary put it), but why?

We are not stupid. We are incredibly smart and we can be amazingly compassionate. What’s more, we are more knowledgeable, connected and empowered than ever before. So why do we act as if we are dumb? Why are we consciously speeding our own demise and the sixth mass extinction?

Mind the Gap

On reflection, I believe that our inaction in the face of sustainability threats is due to a breakdown between causes and effects. Evolution has hardwired us to understand the impact of our actions –fight or flight in the face of danger is a case in point – but sometimes this survival instinct fails. And as far as I can tell, it fails for one of seven reasons:

1. The Time Gap

Our actions now may only have impacts in the future.

So there is a lag or delay between cause and effect. And we would rather choose certain pleasure now, even if it means possible pain from the impacts later. For example, we may choose to smoke or eat an unhealthy diet of fast foods or processed foods today, even though it will most likely cause cancer, obesity, heart disease, diabetes or a stroke later in life.

2. The Distance Gap

Our local actions may only have impacts somewhere else.

Or our actions may impact someone else who we don’t care about. So there is a physical dislocation or an emotional disconnect between cause and effect. For example, we are quite willing to buy a cheap T-shirt from our favourite discount store, even though it probably means it was manufactured under sweatshop conditions in Asia.

3. The Scale Gap

Our individual actions may be fairly benign but still have collectively destructive impacts.

Or we may not believe that changing our individual actions will result in any significant change to our collective impacts. For example, consuming palm-oil (in one-in-ten of the products we buy) does not seem individually irresponsible, even though it is causing tropical rainforest deforestation at a catastrophic scale in Indonesia and Malaysia.

4. The Cost-Benefit Gap

The perceived benefit of our actions may exceed the perceived cost of our impacts (for ourselves or others).

We may also believe we can avoid or isolate ourselves from the impacts of our actions, or mitigate against their effects. For example, the convenience of driving a petrol (gasoline) car seems to far outweigh the effort of cycling, taking a train or the investment cost of buying an electric car, let alone the nebulous future impact of air pollution or climate change.

5. The Causal Gap

The link between our actions and impacts may be unclear, ambiguous or unconvincing.

So the evidence for causality between cause and effect is weak or confused by contradictory opinions. For example, people may wonder: is my consumption of fossil fuel energy really linked to the increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes across the world? Maybe that’s just from El Niño or El Niña. Besides, we just had a cold winter. And wasn’t there some manipulation of the climate data anyway?

6. The Incentive Gap

There may be a lack of incentives to be accountable for the impacts of our actions.

Or there may even be perverse incentives, which nudge us in the wrong direction. So we are not being rewarded or punished appropriately. For example, why should I pay more for sustainable products and green electricity, while the government is subsidising the agro-industrial and fossil fuel companies? And how can I be expected to make long-term decisions for the planet when my shareholders are only looking at the next quarter?

7. The Belief Gap

Accepting the impacts of our actions may contradict our ideological beliefs or vested interests.

So there is a paradigm conflict between cause and effect, resulting in an ‘inconvenient truth’. For example, people may reason: why should we welcome refugees if we believe they are a threat to our security, jobs and culture? Or why become vegetarian or vegan when eating meat is so much a part of our lifestyle and cultural identity?

Bridging the Gap

These seven cause-and-effect gaps are the keys to changing humanity’s kamikaze-like death spiral of self-destruction. For it is only by acknowledging each of these psychological drivers – and finding ways to bridge the gaps they represent – that will stand any chance of overcoming our present failure to act decisively on sustainability. So what might bridging strategies look like? Here are a few ideas to get the ball rolling:

- The Time Gap – Appeal to intergenerational responsibility, since people do care about whether their actions will harm their children and grandchildren’s future. Also, make likely future impacts as visual and visceral as possible, using multi-media.

- The Distance Gap – Encourage educational travel and emphasise our common humanity. Show that someone living in China or South Africa or the United States is really not that different to us; they feel the same emotions and they share similar struggles and aspirations.

- The Scale Gap – Focus on individual responsibility (Gandhi’s ‘be the change you want to see in the world’) and explain how tipping points work, namely that large-scale change can happen when a significant minority changes (research on flocking suggests as little as 10%).

- The Cost–Benefit Gap – Work hard to make the full costs and full benefits clear. This means improving not only the business case for sustainability, but also the personal case and the moral case. We need to get better at ‘selling’ the upside of sustainable living.

- The Causal Gap – Improve the traceability of products and materials and tell the story of products, including their journey across the full life cycle, as Patagonia did with their Footprint Chronicles. Communicate the evidence of causal links between consumption and sustainability impacts.

- The Incentive Gap – Lobby governments to correct perverse incentives, tax unsustainable or irresponsible economic activity and subsidise clean, green and ethical technologies and products. Also, find ways to reward customers for making more sustainable choices.

- The Belief Gap – Expose the vested interests of companies, politicians and the media and challenge inconsistencies between the actions of groups and their professed values. Also, give people a positive alternative belief system. We need a compelling mythology (meta-narrative) of sustainability.

Together, we need to figure out the best strategies for bridging each of these seven gaps and so I welcome your thoughts and suggestions. What have you found works best in engaging people to take action on sustainability? And what doesn’t work? If we learn from each other, we can turn the Age of Stupid into the Age of Inspiration!

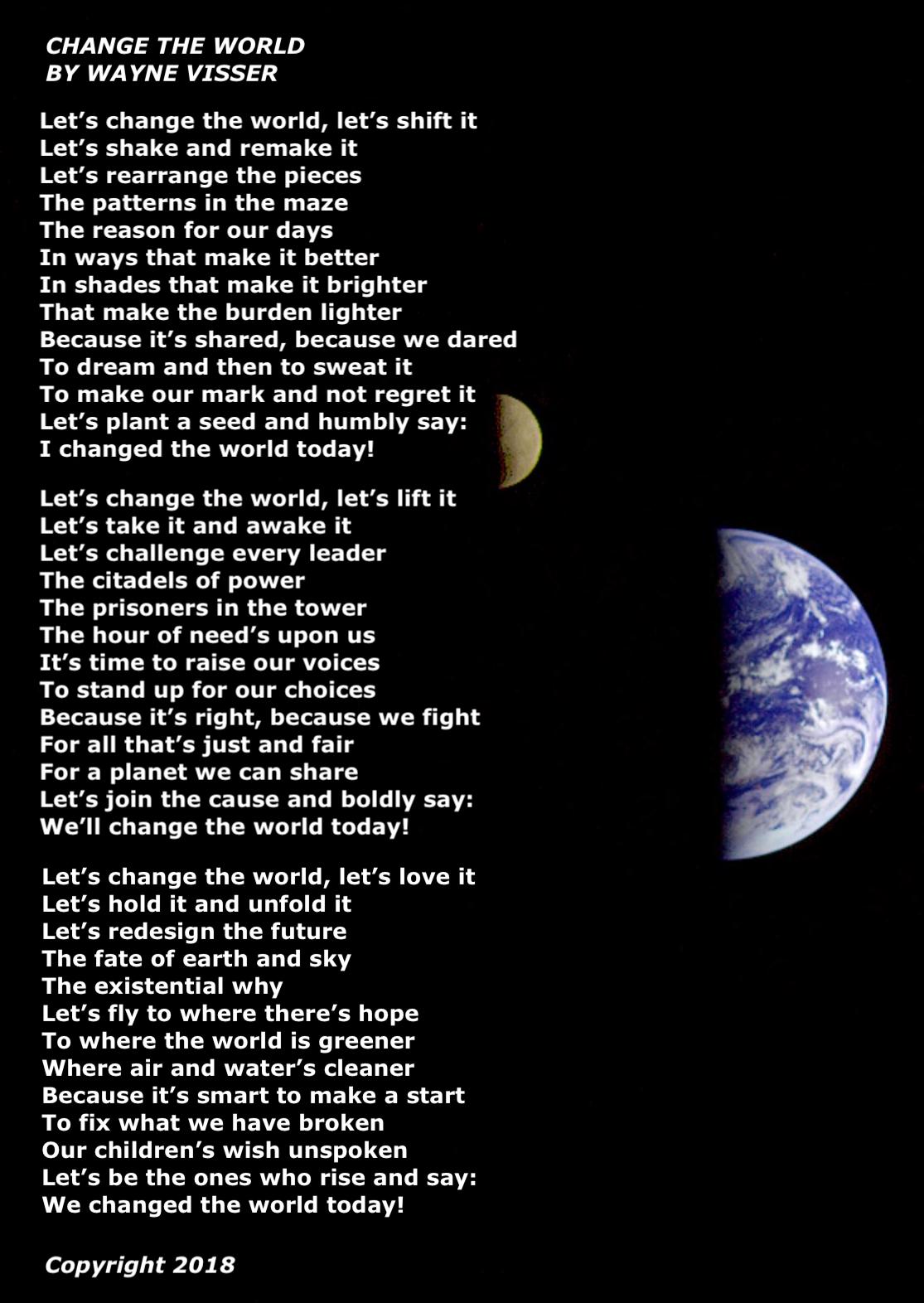

This unique collection brings together poems for positive action by poet and writer, Wayne Visser, providing inspiration for all those who a striving to change the world for the better. The anthology includes perennial favourites such as Be An Optimist, A Place to Thrive, Think on Business, To Lead, Giving Up, It’s Time, A Swirling Story, Because I Care, and, of course, Change the World (Parts 1 and 2), as well as more recent poems like A Butterfly Appeared, The Great Outdoors, and Letter to Earth. Buy the paper book / Buy the e-book.

This unique collection brings together poems for positive action by poet and writer, Wayne Visser, providing inspiration for all those who a striving to change the world for the better. The anthology includes perennial favourites such as Be An Optimist, A Place to Thrive, Think on Business, To Lead, Giving Up, It’s Time, A Swirling Story, Because I Care, and, of course, Change the World (Parts 1 and 2), as well as more recent poems like A Butterfly Appeared, The Great Outdoors, and Letter to Earth. Buy the paper book / Buy the e-book.

This unique collection brings together poems for positive action by poet and writer, Wayne Visser, providing inspiration and motivation for all those who are striving to change the world for the better. The anthology includes perennial favourites such as Be An Optimist, A Place to Thrive, Think on Business, To Lead, Giving Up, It’s Time, A Swirling Story, Because I Care, and, of course, Change the World (Parts 1 and 2), as well as more recent poems like A Butterfly Appeared, The Great Outdoors, and Letter to Earth.

This unique collection brings together poems for positive action by poet and writer, Wayne Visser, providing inspiration and motivation for all those who are striving to change the world for the better. The anthology includes perennial favourites such as Be An Optimist, A Place to Thrive, Think on Business, To Lead, Giving Up, It’s Time, A Swirling Story, Because I Care, and, of course, Change the World (Parts 1 and 2), as well as more recent poems like A Butterfly Appeared, The Great Outdoors, and Letter to Earth.